Not only is Guylaine Sauvaget Lasserre an Assistant Professor at the Psychology department of the University of Toulouse (south-western France), she has also dedicated herself to infant prevention and socialization for twenty years in a state-sponsored French institution. In 2009-2010 she thoroughly advised Master’s student in New Eating Habits Aurore Donnat in conducting her final degree project. Spurred by a strong interest in teenage anorexia Aurore elaborated Le réseau d’Arthur (Arthur’s Network) – an alternative solution to standard single-tray meals through eco-designed packaging. Her aim is to turn mealtimes into good times even for anorexic people.

Guylaine Sauvaget Lasserre was interviewed by Jean-Patrick Péché, Designer, Consultant and Head of the New Eating Habits research unit; their conversation hints at several key issues about design and its role in the food industry.

Guylaine Sauvaget Lasserre

Design as interdisciplinary facilitator

Jean-Patrick Péché: You followed Aurore Donnat’s project from the early stages of its development when she was establishing the preliminary inquiry. Do you find it out of place for a young designer to tackle something as serious an issue as the antagonistic relationship between teenagers and food?

Guylaine Sauvaget-Lasserre: I work closely with the notion of interdisciplinarity. For me, it is paramount that practices and know-how specific to each individual be recognized and interactions and their complementarities be encouraged so as to foster open-mindedness. Should a designer be eager to put his/her skills to use in supporting those struggling with anorexia or bulimia, why should we inhibit that initiative? It goes without saying that the professional must align himself/herself with the objectives and responsibilities inherent to the role of the caregivers involved.

I did not know anything about design, but after observing Aurore’s work, it became apparent that product design stems from a crossbreeding of disciplines. Aurore tapped into the fields of psychology, sociology and, of course, dietetics given her interest in eating habits. The way I see it, design embraces openness and versatility.

Jean-Patrick Péché: As a designer, I love to hear that. In my opinion, design facilitates cross-disciplining.

Guylaine Sauvaget-Lasserre: It can, indeed, facilitate things if it manages to integrate the project as well as combine the interdisciplinary initiatives proposed by players representing a vast palette of fields.

"Arthur's network" : applied arts workshop

Jean-Patrick Péché: On which type of action should we rely to justify the role played by industrial design within the parameters of a project already transversal in nature?

Guylaine Sauvaget-Lasserre: Without overgeneralizing, perhaps we ought to merge with the aims relating to industrial design, though unfamiliar with its detail, which seem to target the best possible rendering of the product in question.

At first, I was puzzled by design’s tendency to gain a foothold in various fields. Then, I realized that for a relatively young discipline, it was important to nurture its potential, and encourage its growth into other sectors.

Jean-Patrick Péché: Yes, that’s the paradox inherent to our profession: Our activities go just as far back to those of engineering and architecture, and yet only the tip of the iceberg in terms of the trade’s notoriety in France has been scraped despite its origins dating back to the birth of industry. The very first designers, devoid of such a title back then, appeared in the early nineteenth century, and strangely, design is still deemed an emerging profession. This is a French paradox whose image is less visible in neighboring countries. That said, this paradox hasn’t kept our industry from evolving or our young peers from finding their own voice in today’s economy.

Design’s potential is limitless despite the general public’s tendency to associate it mostly to the luxury goods market. I am glad to have discovered how design can impact the food sector and latch on to myriad disciplines. A closer look shows design to be far-reaching and versatile.

Art therapy as a way to “give shape to the shapeless” through relationship mediation

Jean-Patrick Péché: That’s absolutely right. You, as a psychologist, took an interest in art therapy. What brought you down this road? What was your motivation? Do you think art therapy contributes, in part, to the way you treat your patients?

Guylaine Sauvaget-Lasserre: Art therapy is, no doubt, a type of psychotherapy, but I am referring here to expressive workshops conducted in therapeutic environments such as those developed by J. Broustra. I began organizing this type of workshop as a result of my interest in group therapy, and after having practiced psychodrama.

Because teenagers often find it hard to only associate words to their feelings during treatment, it becomes interesting to mediate the relationship between them and therapists. I set up therapy sessions during which objects and techniques are transformed into mediating items, including clay, painting, collage, and all that can be handled in visual arts. However, I only resort to this as part of therapeutic schemes with the goal to complement what teenagers express based on what they feel as they yield to the creative process.

When she worked alongside Professor Marcel Rufo, Aurore used the same kinds of techniques and objects to conduct applied art workshops with a very different purpose in mind. From this standpoint, people forge bonds through the item they’re creating and subsequently sharing. This allows for thought not only on the work created but also the culture, an action that is not typically part of the therapeutic field. These are, in fact, two very distinct yet complementary types of intervention, each providing its own insight. Creative workshops − Aurore’s was packaging-oriented − can have an impact on the pathology expressed by the participant to the group, but this is but an induced effect, or rather an outcome of the creative process. Here lies the difference between therapeutic effect and intent.

What I really liked about Aurore’s approach was her following a different methodology from the one she had been taught. This proved to me that a designer is someone who knows how to listen carefully to his/her research object, which happens to target, in this case, teenagers with eating disorders. In her workshop, Aurore’s idea to have participants dissociate container from content related quite well to the issue of anorexia. Anorexia is a rather tricky symptom that primarily affects teenage girls. The body is the symptom’s means of expression. Having worked on the food packaging was a good idea that led to defining a therapeutic effect for the container was reminiscent of the subconscious body image, the body envelope. The container, thus, became a metaphor for the body.

Jean-Patrick Péché: This echoes a significant point in what you’ve said. You used the word “object” to describe what you did during your expressive workshops, and I understood that materializing these objects was a way to either mediate the pathology or the perception that the patient has of it. The notion of “objet” is, undoubtedly, common ground for designers and psychotherapists. Designers are often required to make or shape objects.

Guylaine Sauvaget-Lasserre: In the example I’ve just given to illustrate Aurore’s practice, what is produced during the workshop is to be seen as an “object.”

In my own expressive workshops, form and esthetics do not really matter because what participants produce is but an item to strengthen the bond. To put into words my mediation activities, my motto is, “Give shape to the shapeless.” At the start of my workshops, I never propose a specific shape, but rather those mediators already-mentioned. Aurore, on the other hand, proposes this box. How can a shape emerge from this shapeless matter? I then rely on the concepts of the gestalt, a form-oriented theory. Gestalt can be seen as food for thought between psychology and design.

Jean-Patrick Péché: Would you say that these teenagers, whose relationship to food is rather delicate, have a tendency to exacerbate their perception? Are their senses altered? Do they not perceive things in a different light compared to their peers? Or, on the contrary, do they infuse their perception with new meaning?

Guylaine Sauvaget-Lasserre: Perception and representation are complex issues. To study early-development perceptions, such as food-induced pleasure, it suffices to return to the very roots of the psyche. As my experience with anorexic teenage girls is limited, it is difficult to comment on whether their perception of food is exacerbated. Anorexia is a pathology that affects, first and foremost, the image of one’s body. As I’ve said, anorexia is not only about food and the relationship one has to it. It represents an attack on the subconscious body image, which makes sense when relating back to what I explained earlier as a “…container-based pathology.” Of course, anorexic people’s perceptions are altered because the image they have of their own body is completely unfounded. These girls see themselves as fat, whereas they are not, because the ideal anorexic image leans toward a dismissal of all traces of femininity. Furthermore, all that revolves around lack of pleasure and disgust is, equally, blown out of proportion. Adolescence itself symbolizes exacerbation. Therefore, the question must be examined on a case-by-case basis. Are the young girl’s disorders to be chalked up to the whole teenage phase or, on the contrary, are they triggered by her pathology?

Jean-Patrick Péché: I imagine that this question has given rise to much discussion on the research front. This deeply-embedded pathology prevents those from attaining any type of pleasure. According to Brillat-Savarin, “Taste is the sense that gives us the greatest amount of pleasure.” Are we to deduct from this that the refusal to eat is synonymous with a refusal to achieve pleasure?

Guylaine Sauvaget-Lasserre: These individuals do feel pleasure, though different, for the notion of pleasure is a protean concept. We may encounter a slight misunderstanding due to words that convey different meanings in our respective fields of design and psychology.

For me, an anorexic is on an unquenchable pleasure quest, though not as you would interpret it. I prefer to use the word “enjoyment”, which is different from pleasure. As one can see, even in fields that appear more closely related, such as psychology and psychoanalysis, these terms conjure up very different meanings. I, therefore, don’t think anorexic people can reap any kind of pleasure from food. They can, though, find it in another form during the food-oriented workshops, such as those facilitated by Aurore, from sharing with their peers. I don’t really know how shared pleasure contributes to the design scene, but as Aurore has shown, designers must focus on groups and cliques, “being with others” and the importance of peers because sharing takes root in these kinds of circles.

"Arthur's network": applied arts workshop

Jean-Patrick Péché: Your words strike a chord with a number of projects carried out by our students last year on young adult eating habits, and especially on fruit and vegetable consumption. Together with a sociologist, we observed young people and their eating rituals when in a group setting. This helped us grasp the symbolism inherent to sharing a pizza, a bag of chips, and even in “fake sharing”, or when each youth orders a hamburger, and sits at the same table as his/her friends in a fast food restaurant. This experience proved extremely interesting. This sharing goes beyond what you described earlier. Here’s another question though: As an organizer of visual expression workshops with the same demographics, do you think working with a chef could enhance your current approach with patients?

Guylaine Sauvaget-Lasserre: I don’t think so. It could be interesting, nonetheless, to use these techniques in applied culinary art workshops as chefs bring to the table their respective know-how in fields where caregivers or designers have limited knowledge, such as the molecular structure of food, preparation and presentation. Although not a chef, Aurore observed these teenagers’ daily eating habits at the hospital, and took note of their impressions of the food offered, which included, among others, “bland”, “shapeless”, and “unpleasant.” As a result, she sought to reintroduce a true sensory dimension. We are all different, and our sensory acuity is specific to each one of us. For instance, some teenagers systematically smell their food before eating, which is quite rare.

Design is fed by a connex discipline (psychology) and vice-versa

Jean-Patrick Péché: Let’s get back to Aurore’s work. She first studied teenage behavior and anorexia, and then branched off in the direction of teenage and, in general, young adult eating habits. Her method engendered an approach that meant departing from a pathology in order to learn more about it, as she has demonstrated, to then applying a part of her observations to the design of products or food items aimed at young adults. Does this method seem relevant to you?

Guylaine Sauvaget-Lasserre: Starting from the unique to reach the universal is always relevant, even if the opposite can be said. Considering anorexia to be a specific feature that can serve as a platform for analyzing teenage and adult eating habits seems plausible to me. The goal is to understand how something that failed to be built or was taken apart during a person’s development leads to pathology generation. Focusing on a target population that she had already studied was very clever on Aurore’s part. I was a bit concerned that the experience would be a failure. It seemed next to impossible how a complete novice could gain sufficient know-how to run workshops and devise a relevant design concept. This student worked really hard to make up for her limited knowledge in the field as shown in the quality and consistency of her thesis.

Jean-Patrick Péché: Here’s an interesting point: The problem with design professions is that they are fundamentally transdisciplinary. Knowing this, we need to set limits and assess the skill sets involved. This is why we are interested in having your opinion on how Aurore managed to bring psychology into the picture.

Guylaine Sauvaget-Lasserre: Aurore had both an in-depth and relevant grasp on psychology in that she incorporated the concepts she studied, which can be seen not only in her bibliography, but also in her thesis. Hence, and contrary to anything I’ve witnessed during teaching, Aurore seemed very open to other subject areas, and exhibited a mindset that is to be encouraged and nurtured.

Architecture of the "Arthur's network" service

Jean-Patrick Péché: Indeed, we strive to instill open-mindedness in the students. Designers have little to no information regarding an issue, and are not in a position to project any kind of ego prior to understanding what the issue entails. This attitude is central to our teaching methods.

We mentioned the notion of the “object” and its ability to mediate the relationship between a patient and therapist. Do you think there exist more knowledge-sharing opportunities between designers and psychologists?

Guylaine Sauvaget-Lasserre: Why not? Interesting collaborations could come from this considering that by focusing on an individual’s mental process with regard to a specific field can only benefit the designer and the needs analysis performed, which, in turn, will provide a clearer idea of the project design process. In psychology, like in design, there are many schools of thought. Some psychologists are labeled cognitivists or behavioralists, whereas others, like myself, rely more on psychoanalysis, which explains why I tend to always focus on the “subject.” Since these tendencies lay the foundations for different types of philosophies, designers should choose their partners carefully based on their respective credo.

Jean-Patrick Péché: You seem to have hit the nail on the head. Designers often go above and beyond the demands outlined in the specifications.

You have a good overview of creative professions. Would you say that your interest in art and visual expression as well as for your work as a therapist have impacted your relationship to art and creation?

Guylaine Sauvaget-Lasserre: Taking in art in all its forms, whether it be going to the museum, exhibitions, reading, listening to and playing music, etc. is food for thought, and means to a greater awareness of feelings. The self-improvement is something on which I like to rely in my creative workshops where the object targets a finished product. It is only then when we can “produce art in the style of” a renowned artist, mimic his/her techniques, adopt but a part of what he/she has developed, which, in turn, transforms and enhances our own creations.

That said, as in the therapy-oriented workshops I lead, the aim is not to produce art, but to have the participants yield to their emotions, feelings, and whatever else affects them along the way during the production process.

Aurore Donnat – Le réseau d’Arthur (Arthur’s Network) by Jocelyne Le Bœuf, Head of Studies

Helping young adults – especially those suffering from anorexia – adopt healthy eating habits in teen treatment centers.

Inside a department specializing in adolescent pathology

Aurore Donnat spent several days immersed in “l’espace Arthur”, housed in the department headed by Professor Rufo (1) at the Sainte-Marguerite Hospital in Marseilles, observing the day-to-day and conducting workshops. This enabled her to think in depth about the role design could play in teaching teenagers with eating disorders on how to feed themselves. Her research had her step into an innovation-friendly field. “L’espace d’Arthur” is a place where new care systems are undergoing experimentation (2), and where young patients are brought together “…not because of their disease nor the type of suffering they’re experiencing, but simply because they are teenagers, and therefore, going through major changes in their lives.”

In her food-oriented workshops, Aurore Donnat focused on sensory issues with a view to deciphering the link between teenagers, food and eating rituals. She noticed to what extent single-tray meals served by institutional food services were abhorred by her target audience – the steam on pre-cooked dishes’ packaging, reminiscent of sweat, repulsed them. She noted which new and original recipes appealed to and repelled her participants. She also conducted applied arts workshops during which she assessed the impact of packaging by addressing the notions of materials and graphic codes.

In addition to her fieldwork, she conducted documentary research about taste and how it is shaped, about child and adolescent development and about the diverse approaches to mental anorexia.

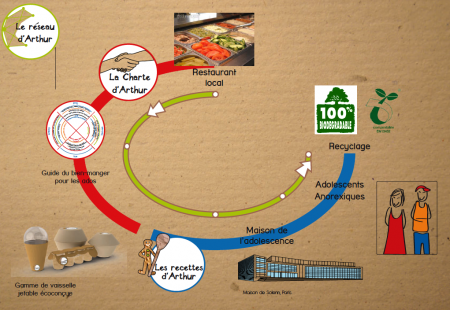

Le réseau d’Arthur (Arthur’s Network)

This project aims to find an alternative solution to classic, single-tray meals, which convey a derogatory image of institutional food services, be it packaging- or content-wise. It has brought to life a new, ever-growing network within which collective food services are gradually replaced with locally grounded cuisine. A charter was written to promote teenager-adapted recipes. The new eco-designed packaging pieces are shaped so as to recall snacks. As eating is not just about feeding oneself, “Le Réseau d’Arthur” intends to turn mealtime into a good time that anorexic teenagers could actually enjoy and even look forward to.

Notes:

1 – Marcel Rufo, La vie en désordre : voyage en adolescence, éditions Anne Carrière, 2007.

2 – These new care systems are being implemented in teen treatment centers (maisons de l’adolescence) such as the Paris-based Maison de Solenn – http://www.mda.aphp.fr .

0 comment

Leave a comment