Interview with Thomas Bottini, researcher in computer science for music

“Knowledge Transfer(s): the interviews

Since 2008, CADI has investigated the field of knowledge transfer by interviewing experts who agreed to supervize fifth-year students in carrying out their final degree projects. This is an effort to build up a corpus of testimonies to come to a better understanding of the collaborative and representative methods resorted to by innovation and creation players, taking into account economic, cultural and evrironmental trends. In March 2010, we evolved the print issues into an electronic…

Thomas Bottini holds a degree in computer engineering from the Technological University of Compiègne (France). In parallel to his engineering training, he studied human sciences and the philosophy of artistic creation-related content. His current research into creating tools for the advanced reading and writing of multimedia documents demonstrates his keen interest in studying the relationship between digital technology and artistic creation. To further study this link, he has worked in collaboration with musicologists from the IRCAM (French institute of research and musical/acoustic coordination) to develop as a cross-disciplinary team a multimedia environment dedicated to musical analysis. In 2006 he created a tool to help organize musical analysis in tables (Musique Lab Annotation).

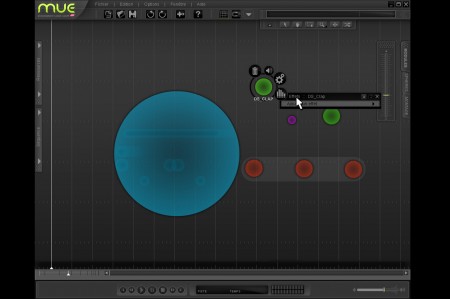

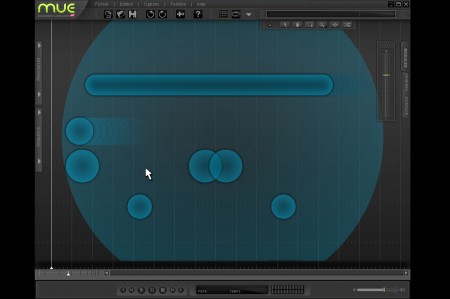

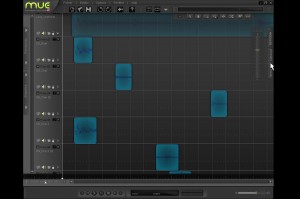

MUE - Auréien Pasquier's final degree project carried out with the help of Thomas Bottini, 2008-2009

Computer music and real/virtual paradox

CADI: What is computer music? What type of people use it?

T.B: Computer music encompasses several fields. But I suggest we stick to computer-aided composition since this was the main theme underlying Aurélien Pasquier’s project. This method dates back to the fifties when researchers from the big American universities began to analyze existing music pieces in an automatic way. Their research paved the way towards new music-generating composition tools which can be categorized into two different approaches: the musical approach and the acoustic approach. With the musical approach, computers are used to generate musical structures (notes, melodies, variations, tunes, etc.). It is therefore writing-based. The acoustic approach has more to do with sound synthesis and creating new sounds so as to keep treading upon new soundscapes. The tension between these two dimensions – between musical speech embodied by notes on the one hand, and the sound bodies through which they take shape (i.e. the acoustic dimension of musical speech) on the other hand – is essential to understanding computer music and indeed music in general. More simply, it concerns the tension between “abstract” and “concrete” dimensions. Computer music has only reinforced the necessity to become aware of the binary pattern underlying music. Over the last sixty years or so, many research projects have been jointly conducted in these two complementary fields. On one side synthesizers have evolved and have even ensconced themselves within computers (some software-based synthesizers are just as powerful as hardware ones): this is the acoustic approach. On the other side writing tools help give concrete expression to musical ideas and provide some kind of enhanced music scores for writing melodies and tunes and handling musical structures and are not solely for generating sounds. The tune writing device developed by Aurélien ranks in this category.

Some tools blend these two main functions. Reason, which you mentioned earlier, offers a wide spectrum of functions both in terms of synthesis and simple musical structure, which allows users to compose a musical piece from A to Z. However, as it has been marketed to a very broad audience as a “simplistic electronic music” device, it fails to impose itself as a groundbreaking tool and to exploit the tremendous potential of digital environments.

CADI: In his final thesis Aurélien addresses the real/virtual paradox of those tools which, though virtual, strive to imitate the modes of interaction of real-life devices, thereby limiting their own possibilities.

T.B: The issue of virtual systems seen as metaphors of the real world is one of my main research and teaching topics. Computers offer tremendous possibilities which, unfortunately, cannot easily nor immediately be understood or perceived by users. Manufacturers are thus endeavoring to immerse users in interfaces that echo familiar devices. This explains why computer software – though often very complex – often imitates real-world tools, such as mixing tables, cables, switches and synthesizer potentiometers. However, this is a pity because on a functional level digital “virtual” tools are way more versatile and give more outstanding results than “real” tools. Yet as people are not yet attuned to the physical and aesthetic representation of these functions, they stick to those they are familiar with. This quite simplistic way of handling things totally prevents us from realizing how much power lies within computers.

MUE - Auréien Pasquier's final degree project carried out with the help of Thomas Bottini, 2008-2009

CADI: What are the main lines of research in the field of computer music applied to creation and computer-assisted musical composition?

T.B: Computer music is a fairly complex and cross-disciplinary environment. Therefore your question could be answered in about a hundred different ways. Computer capacities have increased so much over the past sixty years that these tools could potentially become a real puzzle for end-users. The aim is to design clear, easy-to-use and easy-to-understand interfaces that make the most of the huge array of functions. We should stop just trying to find ever-more powerful synthesis algorithms – technically we now have the means to do anything we want. Our real mission is to understand which interfaces, which representations and which types of body language should be implemented to enable users to interact with the wide range of functions available. For now, this objective is not within close reach, primarily because we still use rigid, tedious and ill-conceived working tools. So far, only very few designers and ergonomists have actually studied this type of tools. We’re just getting started and a lot of work still lies ahead.

“Tools must not remove human intelligence”

CADI: So the real challenge is to create interfaces that are easy to use?

T.B: Before facilitating use we should first design an interface that would give users a clearer picture of the devices they are handling. Synthesizers are fitted with rows of buttons that all have their own specific function so users can easily understand how they work. However on computers, users often have to navigate through multi-branched and very complex menus which are difficult to grasp on a sensory and sensitive level. Therefore before we even decide to guide users we must first bring them to some sort of sensory awareness of the tool they are using.

CADI: What role could designers play in this context?

T.B: To this day they’ve only played a very small part in our field of activity: this industry is not really an industry so to speak and it only represents a tiny share of the market. It is for the most part composed of small underground companies – with only a handful of research projects and employees hidden in a basement, who play around with ideas and techniques. From what I’ve seen, not even the slightest notion of ergonomics or design has so far been applied to this type of tools. Thus, this field really needs to be explored. One day I still hope to see the domains of computing, music and design working together to come up with user-friendly tools which are more adapted to the needs of both amateurs and well-seasoned composers.

CADI: We shouldn’t fall into the trap of over-simplification either.

T.B: To avoid this, we must strive to design smart interfaces that enable people to understand the workings of the tools they use without oversimplifying these tools in the process. A good example of this simplification is the metaphor offered by the software Reason, which mimics actual real-world tools in order to avoid unsettling users.

CADI: The term “smart interface” requires further explanation. How would you define it?

T.B: One thing is certain: a smart interface is not meant to replace the user’s brain and thinking abilities nor to carry out tasks on its own. It would not make any sense to design such interfaces. It is not a case of removing human intelligence. Human beings need to be assisted in their thought process by being provided with representations, objects or procedures that will act as incentives for their imagination, as Boulez stated. Musical composition and writing devices must be made into true extensions of the limbs and of the whole body, like musical instruments. To do so, we must not create tools that take over the user’s brain but rather ones that can assist human thought by becoming an integral part of their gestural and cognitive flow.

CADI: Is it at this stage that designers should bring in their useful human-centered input?

T.B: In an ideal world it would probably be so. But for the time being no designer has ever actually put his/her knowledge into practice in musical creation – here I mean the tools used by composers. Their skills are only put to use in research tools or in industrially-manufactured tools marketed by huge companies with a small concern for research in design. These types of structures are blatantly lacking in innovative initiatives. It seems like innovation blossoms more in human-sized companies where employees, though not designers, come up with relevant ideas and dare to experiment with new, more inventive modes of representation.

This would be great. But for now, functional innovation, i.e. the type of innovation giving shape to new ways of making and thinking in musical creation, has only aroused the interest of a handful of research labs and small innovative companies. These small firms, eager to explore new ideas and who dare to propose inventive modes of representation, probably cannot afford to implement the hefty design studies required to further their proposals and develop their uses. On the downside, the more prosperous large industrial companies seem to turn a blind eye to their own need for design. As a result, they fail to revamp their models and continue to feed us the same old interfaces over and over ( tracks, virtual mixing-tables, etc.).

MUE - Auréien Pasquier's final degree project carried out with the help of Thomas Bottini, 2008-2009

Down with mimicking the real-world in computer music

CADI: Though computer technologies keep evolving, interfaces remain the same and fail to achieve enhanced performances. What exactly appealed to you in Aurélien Pasquier’s project MUE – a device created to enhance the sound and visual experience provided by computer-aided musical composition interfaces and to strike up a bond between computer tools and the subconscious of music fiends?

T.B: Originally, the premise of the project aroused my interest because it seemed to provide a relevant analysis of the situation. It is a well-known fact that today representation is a real problem in most computer tools: the metaphor which mimics real-world devices is too restrictive and therefore does not work. I am convinced that to remedy this situation we must carry out as many experiments as we can. After this first insight into his project, I discovered what Aurélien had actually done and realized that he had come up with quite a number of very smart enhanced interface solutions fit to be industrially manufactured (especially concerning the way new modules can interact with one another in a coherent environment. Some of the ideas he brought to the fore concerning representation and interaction principles are rooted in an innovative approach to technology led by a designer who is ahead of his time. Thanks to the skills in graphic design he acquired during his training course he has gained a good understanding of how to exploit onscreen bi-dimensional space to represent musical devices. Tools for writing music are often quite rigid and composed of devices that always prove difficult to visualize and use onscreen. Aurélien came up with a few representational paradigms obtained through a clever use of the bi-dimensional nature of space. Thanks to these paradigms users can discover a new type of representation and therefore cast new light on the work they are in the process of writing. A mode of representation is never completely neutral, it always effects what we do and how we do it.

A musical environment is always comprised of numerous elements (sound matter, sound treatments, tools to adjust acoustic and musical features, parameter control devices, etc.). But amid this proliferation of instruments, the main challenge in terms of cognitive and gesture-related issues lies in how the interaction between concrete and abstract, between sound and music and between instrumentation and structures is understood and used by the composer. So far traditional sequencers have handled the switch from abstract to concrete sound very badly. Sound-generating and note-organizing tools are too often simply stacked upon another without anyone giving much thought to the link between the two. Speaking of which, Aurélien invented one or two representational paradigms that enable users to control values and to have greater control over effects. He has implemented an interesting type of object which solves one of the main issues posed by computer music: the link between abstract and concrete, which is brought to the fore by the interaction between the acoustic and musical dimensions.

CADI: Does Aurélien’s project seem industrially feasible to you?

T.B: Very much so, particularly as Aurélien has never had any musical training. Therefore, if he were to work in collaboration with signal experts and composition-literate users, he could design an object which is far more advanced than most existing ones. This student has created a sound concept. A profile like his – one that combines both technical and artistic skills – is not that easy to find. In the field of computer music development such skills and sensitivity in graphic design are quite rare.

Industrial lock-ip, inertia, open source? What scenarios for tomorrow?

CADI: Music has always relied on technical and technological evolutions. Over the past few decades, new digital technologies have led to tremendous upheavals in music perception (listening and composition) and interaction with music. As an engineer, what type of developments do you think music, musical tools and musical environments are about to go through?

T.B: Let’s play psychic and predict the future then. There are several possible scenarios. In the first one the industrial world would totally close upon itself because market leaders would crush anyone making the slightest attempt at innovating. This scenario would simply be a follow-up to the current situation. Indeed, outside the non-professional sphere, no one uses computer-aided musical devices except for the big tools used in large recording studios. In my opinion this is quite a shameful situation because these big companies are driven by studio-related functional requirements that prevent them from giving free rein to their creativity as far as design is concerned. Of course, inertia would be the worst-case scenario. The true challenge in this field of activity is to understand and properly handle the transition between analog and digital material. Studios are equipped with analog devices and therefore digital technology fails to find a slot within the composition process itself. In fine, users remain stuck to their mixing table, using hardware synthesizers. This is quicker and enables users to work collectively in the same room. I really doubt that in-studio music creation and mixing is going to change drastically in the near future because analog techniques have become so ingrained in this field that they have imposed their concepts upon many digital tools. Digital technologies keep gaining ground in studios, opening up new horizons for the profession, reconfiguring already existing methods, but it fails to bring about great shifts in the representational paradigms underlying musical tools.

However, I am more interested in amateur practices than in the professional world. My research activities are centered upon non-professional users who interact with all the devices in their home-studios, and upon the various possibilities they dispose of, be it composing / writing or reading / listening. In this field things are definitely going to move ahead. The amateur field is not closed upon itself nor rigidly corseted by age-old traditions and the domination of a handful of players (like Pro Tools, for instance), and therefore it should undergo significant evolutions. Furthermore because of overpriced material, alternative economic solutions such as open source software are gradually being implemented, making it easier for many revolutionary tools to become more widespread. Unlike the studio environment, this field has not yet reached stability, and we are just witnessing the prehistory of amateur-oriented computer music (“amateur” used here as in one who is fond of something – from the French word “aimer,” meaning “to love”– and not in the sense of incompetent). Radical changes are already underway. We must opt for open source, an ever-developing solution in musical computing whose dynamic, vibrant nature facilitates collaboration and offers more flexibility than proprietary software. Secondly, we must also ask ourselves how to recreate cross-disciplinary working structures in the midst of this utterly fragmented economic model. The real challenge on a theoretical level lies in sparking off collaborations between people from different intellectual backgrounds. These types of exchanges need to be part of a clear framework, which aims to promote collaboration between designers and sociologists, musicians and technicians. I am positive this type of interaction is the key to rewarding innovation.

CADI: How could design contribute to the prospective scenarios you have just described?

T.B: In my view design is the link between technique and use. Design is what spurs users to adopt new technical tools. Indeed manufacturers failing to give some thought to design-related issues will have a hard time making users adopt new technical tools. One question has been nagging me for quite a while: how could we introduce design-related research into such a decentralized, fragmented economic model, in which roles are not clearly defined. To me, the most inventive projects are always rooted in open source software, but as soon as we begin to perceive their innovation, numerous questions arise about the structures that enable us to further and promote the projects. We often try to think about how to involve a designer in our activities. Let us keep in mind that in our field of activity money tends to be quite scarce…

In my view, the main challenges to confront in the near future, if we really want the technical devices in the artistic field to move on, lies in the creation of small cross-disciplinary collaborative structures. These structures would bring together designers, engineers and creative professionals or artists. As far as computer music is concerned, for instance, we will imperatively have to work in collaboration with composers who, being the primary users of the devices we will be designing will be in a position to tell us more about their current and future needs. Indeed, the aim is not only to identify and satisfy a need, we must also anticipate potential needs and innovate. Innovation is a very complex factor that proves extremely hard to define because it lies at the junction between the work of practitioners, technicians and designers; it is a very versatile phenomenon lying at the crossroads of all these approaches to production.

CADI: It seems like musicians who use computer-aided composition tools simply accept their fate. Designers – whose role also implies making users aware of their discomfort – could encourage those who are fond of these types of software to revise their standards upwards.

T.B: Most users simply take what is already there and try to make the best of it because they know they’re lucky enough to have access to those devices. As a researcher, I am always looking for something new and always seeking a better solution. But we should not overlook the fact that the already existing tools are quite formative and make it possible to develop uses which were totally unheard of ten years ago. At some point you get lost and confused with these technologies. Sometimes we spend more time looking for the perfect tool than using the one we have.

Interview conducted by Morgane SAYSANA, Editorial Coordinator.

More about Aurélien Pasquier’s project – MUE

Dematerialization triggered by the advent of digital production tools has greatly modified the way we perceive and play music. No matter how hard the, sometimes amateur, musical software industry has endeavored to devise the right metaphors for composition and sound cutting/ editing, it has more than often failed in the process. In a field of activity where amateurs and professionals work in the same technological environments, Aurélien took a clever stance by guiding users according to their level of expertise, using an innovative crystal-clear interface.

To complete his project, Aurélien followed three main avenues of reflection. Firstly, the will to do away with interfaces that awkwardly imitate existing analogical tools and to devise modes of interaction and visualization, which are better adapted to the sound being worked upon. Secondly, the will to group together all the various tools so as to offer users a smoother creative process, whether it be in musical composition, audio composition or musical creation, making it easier to hop from one step to the next. And finally, the desire to design a tool which is able to adapt gradually to the user and to their level of expertise especially by analyzing in depth how the software is actually being used.

These three main lines were brilliantly intertwined into a simple and stylish interface, which was particularly suitable for tangible interfaces (such as multipoint touchscreens), making the process of musical creation more malleable, without sacrificing the precision and accuracy required for real professional use.

F. Degouzon – Head of the Strategy, Research & Development Department

Aurélien Pasquier – 06 71 38 96 92 – aur.pasquier@gmail.com

0 comment

Leave a comment